“Field of Fire”

7.13 (aired February 10, 1999)

“I am certain you will do whatever is necessary to complete your task.”

“And how do you know that?”

“You’re Dax. It is your way.”

— Worf and Dax

Remember when Ned Flanders was just Homer’s relatively normal neighbor? Flanders was even-keeled where Homer would fly off the handle. Flanders was upwardly mobile, while Homer was stuck in a dead-end job. Flanders had well-behaved kids while Homer had, well, Bart. He existed as a foil for Homer, a man for whom life was easy, who could antagonize Homer just by being pleasant. Somewhere along the way, the writers decided that, to contrast Homer’s rocky relationship with religion, Ned should be a committed Christian. And that’s where things spun out of control.

In all of Ned’s subsequent appearances, his Christianity became more and more important until it was his defining characteristic. We human beings are a simplistic bunch, and we’re always looking for a single magic bullet to describe something as complex and contradictory as a human being. Writers are no different, especially while working on anything longform. So, Ned Flanders turned from the kind of person who attended church on Sundays to the kind of person the protagonists of the Left Behind series might call “a little too Bibley.”

This phenomenon, of steadily exaggerating a single character trait at the expense of others even has a name: Flanderization. It’s fairly common across all media, though it’s especially prevalent in sitcoms. In the beginning of Friends, Joey was merely an affable but book-dumb actor; by the end of the series, he seemed legitimately mentally challenged. As much as I praise the writing on DS9, it happened here, although to one of the most unlikely characters. Even stranger, it happened all at once, as though the writers forgot who this guy was supposed to be and were like, “Forget it, he’s Hannibal Lector.”

I’m referring to Joran Dax, the “lost” Dax host introduced in season three’s “Equilibrium.” The idea behind that episode was that since Joran, a violent and unstable man, could be successfully joined for a time, a much larger proportion of the Trill population could therefore be joined safely. The Symbiosis Commission was hiding this out of a desire to protect the symbionts. In the story, Joran commits at least one murder, but the episode implies it to be a crime of passion and desperation, undertaken by a damaged man.

By the time the character reappears at the tail end of the third season in “Facets,” (this time being incarnated in Sisko’s body), he’s just a straight-up psychopath. I have no idea how the Joran of “Facets” managed to convince the Symbiosis Commission he wasn’t an unhinged murderer. The guy opens his mouth, and I’m already wondering how many human skin lamps he has in his home. In the eighteen episodes between “Equilibrium” and “Facets,” Joran was Flanderized largely beyond recognition. He went from Jerry Lundegaard to Ted Bundy.

This week’s episode brings Joran back, trying to bridge the two incarnations of the character. He’s not quite the hockey-masked villain of “Facets,” but he certainly isn’t the tragic murderer of “Equilibrium.” If it seems out of place to do a character piece on a Dax host, it is. The episode was produced largely because they had one they needed to fill (Remember that mad 26-episode order.), and no one on the writing staff available to do it. Ira Steven Behr brought back his old partner, Robert Hewitt Wolfe (who left at the end of season five) to do a story about Odo tracking a serial killer. Wolfe decided that since we’ve seen Odo find killers before, we should see it through a new character’s eyes. So, he chose Ezri. In the process, he wrote Silence of the Lambs. Okay, that’s unfair. He wrote a combination of Silence of the Lambs and Red Dragon.

It would be difficult to overstate the volcanic influence the works of Thomas Harris had on pop culture in the ‘90s. Silence of the Lambs was a formative film for me (probably says a lot there) and went on to calcify a lot of the tropes we use in serial killer fiction. In the Charlie Kaufman film, Adaptation, the mercurial and brilliant writer blasts serial killers as one of the most hackneyed tropes in all of fiction, and he’s not wrong. Largely because of Silence of the Lambs and all the films and TV shows that sprang out of it. So, what should feel bracing and new instead feels shopworn. Ironically, it took yet another Harris adaptation, Bryan Fuller’s gorgeously gory Hannibal, to bring serial killers back to artistic relevance.

While every member of the crew does what they can to help, it’s up to Ezri, the counselor, to come up with a profile. Joran immediately surfaces in her subconscious, trying to get her to use him as a resource. She initially resists, but ends up using a variation on the zhian’tara ritual (seen in “Facets”) to allow the memories of Joran to surface. He acts as Hannibal here for her, trying to get her to “think like a killer,” and the various other hoary cliches serial killer fiction relies on.

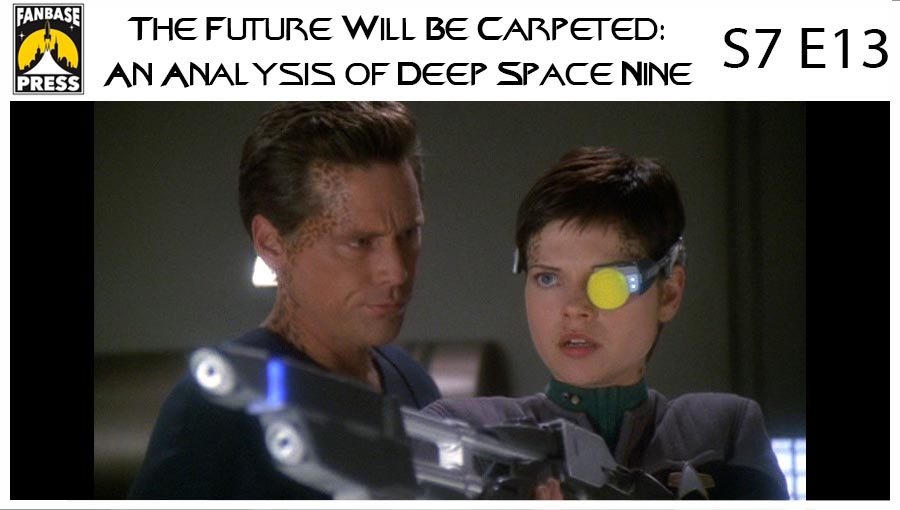

The victims have no obvious connection until Ezri finds it in one of the silliest scenes in the series. Using a series of whooshing cuts, she goes from quarters to quarters, pointing out that each victim had a photo of themselves laughing with someone. She hypothesizes that it has to be a Vulcan who suffered a severe loss, and yeah, it’s as flimsy as it sounds. But she’s right, and it leads to the one good scene in the episode, which owes a heavy debt to the thrilling showdown with Buffalo Bill, where Ezri and the killer have a showdown with transporter-equipped rifles and targeting devices that see through walls. Ezri makes the shot, but she doesn’t kill him. Her triumph is accepting Joran’s presence, but not becoming a killer herself.

I’ve already said this is the low point of season seven for me. It’s much better than the low points of other seasons, to be certain. The chief fault of this episode is being merely a nest of cliches. It’s still reasonably diverting, it largely works dramatically, and it has a thrilling ending. Consistency, though, isn’t its strong suit. This Joran is a new invention, becoming what the writers needed him to be. Ironically, the most consistent thing about him is the way he holds his hands behind his back, a trait all of Dax’s subsequent hosts received from its first, the politician Lela. It’s a level of nuance and care out of place in this otherwise ersatz creation. Fortunately, this is only a minor bump as the show barrels toward its thrilling ten-part conclusion.

Next up: Odo gets an unexpected visitor.